The surprising reason why French people eat horses

The other night I was reading Black Beauty to the enfants and, when we got to the bit where (SPOILER) Ginger dies, my smallest had to take over reading duties because I was bawling so much. Growing up I had riding lessons (limited success), horse posters on my walls and wouldn’t go anywhere without my stable of imaginary horses. It’s fair to say that I hold the beasts in some affection.

In Britain, we only eat horse meat by accident or deception, which is why it shocked me the first time – and saddens me to this day – to see the horse meat stall at our local market in France. Rightly or wrongly, British people view horses differently from cows, sheep and pigs. So why do the French, a people culturally and geographically close to the British, eat horses?

It wasn’t always like this. An eighth-century pope banned horse eating in Christian countries – not out of concern for horse wellbeing – but because it was associated with paganism, particularly among German tribes.

Not only was selling horsemeat was illegal in France, there was also a taboo around it. Eating horses was associated with ill health and poverty. When people did do it, it was generally because they were missold the meat – exactly as happened in the 2013 horsemeat scandal.

Like many things in France, however, everything changed with the revolution. In 1789, the aristocracy had fallen, and their property redistributed and repurposed – including their horses. Once status symbols, the horses of the rich and powerful were now used to feed the starving masses. Let them eat horse, if you will.

This was followed, in the nineteenth century, by a series of miliary oopsies (not a technical term) which saw French troops, cut off from supplies, driven by desperation to eating their horses. At the Battle of Eylau of 1807, Napoleon fed his troops horse soup seasoned with gunpowder.

At the same time, a zoologist and a military veterinarian, who had seen troops saved from starvation by horsemeat, were trying to persuade Parisians – and the government – that horsemeat was a fine alternative to beef or pork. The cost of living in Paris was exorbitant and many ordinary Parisians couldn’t afford meat – indeed, many were starving and horsemeat was a cheap and abundant source of nutrition. Grand banquets featuring horsemeat dishes were organised to try to convince the public of its merits.

The second, perhaps more surprising, argument was that it was kinder for working horses to be killed and used for meat, rather than to be worked to death. And, going back to Black Beauty and its heart-rending descriptions of the brutality suffered by working horses in nineteenth century London, it is hard to disagree. La Société protectrice des animaux (SPA) was one of the supporters of the consumption of horse meat for this very reason.

In 1866, the French government legalised the sale of horsemeat and the first boucherie chevaline opened in Nancy, followed two weeks later by another in Paris. Horsemeat could only be sold in these specialist outlets and they frequently had prominent signs featuring horse heads so that shoppers didn’t confuse them with ordinary butcher’s shops.

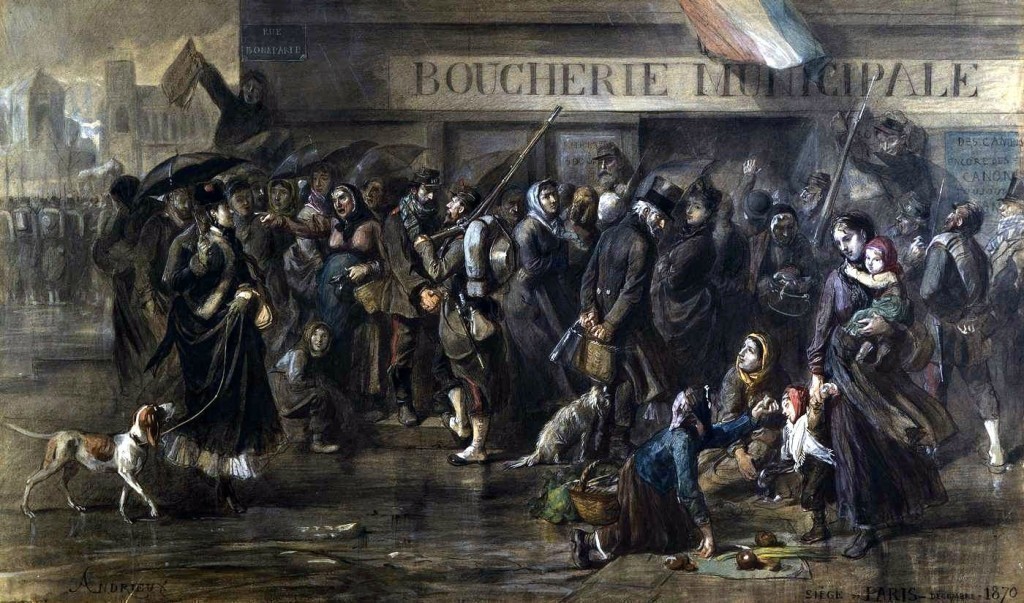

Just four years later, an event took place that would turbo-boost the already softening attitude towards the consumption of horses. It was the brutal, devastating siege of Paris. The city was surrounded by Prussian forces for four long months and, cut off from supplies, the city’s resources dwindled to the extent that people were driven to extremes of hunger. Horses were the first. Not only was their meat similar to beef, but the grain that they would have eaten could be used to feed people. At the beginning of the siege in September, there were 100,000 horses in Paris; two months later there 70,000.

Horsemeat wasn’t enough. In L’Année terrible, Victor Hugo recounts the experience of living in the city at this time, and the extents to which people were driven to survive.

Nous mangeons du cheval, du rat, de l’ours, de l’âne… (We eat horse, rat, bear, donkey…)

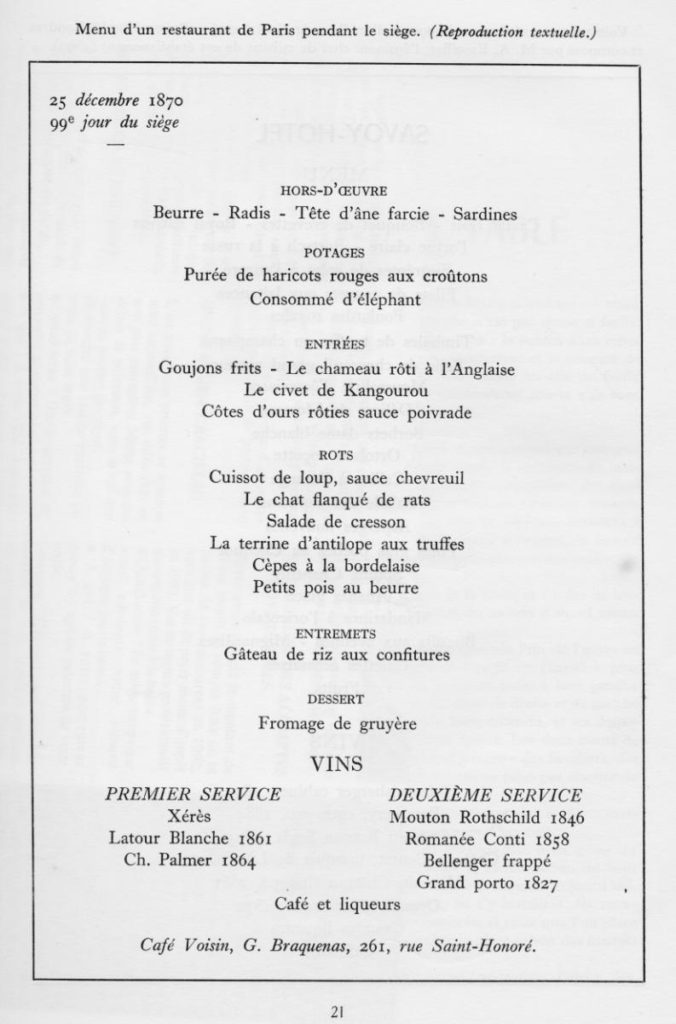

Yes, “bear”. Notoriously, zoo animals found themselves on the menu of a restaurant at Christmas. On the menu – the 99th day of the siege – is elephant soup, roast camel, kangaroo stew, bear ribs in a pepper sauce, wolf with a deer sauce, cat served with rats and antelope paté. By comparison, eating horsemeat hardly raises an eyebrow.

The siege ended but the taste for horsemeat did not. Far from being considered a meat chosen only by the desperate, it was praised for being a healthy choice, low in fat and full of iron. It even became popular wisdom to feed horse soup to people suffering from tuberculosis. By 1905, at its peak, there were 311 horse meat butchers shops and around 200 market stalls in Paris alone.

For the first part of the 20th century, horsemeat was a popular choice at the French dinnertable but its consumption has been diminishing steadily since. The last 20 years have been catastrophic for horse butchers with a 75% drop in purchases. Only nine percent of households bought horse meat in 2019 – half that of 10 years earlier. Not only are fewer people buying it, they are also buying less, just 2kg of horse meat compared with 10kg of beef.

Then there’s the people buying it. 80% of purchases of horsemeat was made by the over 50’s. It seems that it’s not a meat the appeals to younger French consummers.

What’s behind this change? One reason is price. Horse meat became popular in the 19th century as a cheap alternative to beef. Today, that position is reversed; only veal is more expensive than horse meat. 29% of non-purchasers said they don’t buy it because it’s too expensive or difficult to find. This final point is easy to understand as there are far fewer horse butchers in France nowadays. In 2019, there were 304 boucheries chevaline in France, down from over 1,000 in 2005.

But the other, far greater reason, for French people not buying horse meat is their attitude towards the animal. 61% said they would not eat horsemeat for ethical or religious reasons.

While at the beginning of the 20th century, horses were animals of labour, gradually they have become associated more with sport and leisure. As emotional bonds between humans and animals get stronger, it get harder to consider them as a source of food.

It was a popular meat for a long time. And then horse-riding became very popular and the image of the animal changed. An emotional relationship has been created.

The vast majority of French people no longer eat horsemeat. They’re not even the biggest consumers in Europe – that dubious honour goes to the Belgians or the Italians, depending on what statistic you’re looking at. And we British can’t feel too smug about the situation either. While we may not eat horsemeat, around 10,000 British horses and ponies are slaughtered and exported as meat each year.

I’ll leave the last word on the subject to the author of Black Beauty herself.

We call them dumb animals, and so they are, for they cannot tell us how they feel, but they do not suffer less because they have no words.

Sources

Les consommateurs de viande chevaline en France (Septembre 2020)

Nantes: Boucher chevalin, une profession en voie de disparition

Viande de cheval : une consommation marginale