The Hysteria Show

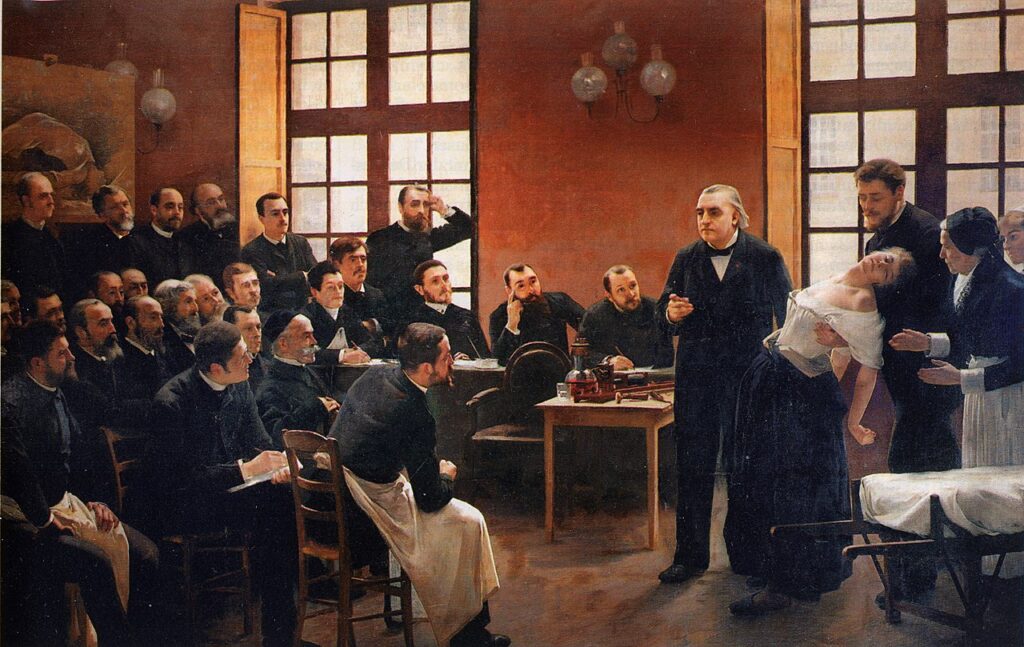

An insane asylum is an unlikely setting for a hit show. And, true enough, drawing crowds was never the intention of the show’s brilliant creator, but it was undeniable that the lecture theatre at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris was never fuller than when its female patients were hypnotised into compliance, then exhibited before an audience. And what a audience. It was made up for the most part by men of science, naturally enough (the young Sigmund Freud was an enthusiastic spectator), but artists, writers, actors and aristocrats gleefully jostled for space with these duller attendees – the spectacle was worth it. The word on the street was that Blanche, the show’s star, was capable of displaying more pure emotion under hypnosis than the greatest stage performer of the age. Sarah Bernhardt, the intended recipient of this barb, made sure to see her rival in action, and confessed to having been influenced by Blanche for a later role.

It was this demonstration of raw feeling that entranced audiences. Dr Jean-Martin Charcot, director of both the hospital and the show, had found a way of accessing and controlling the emotional state in his female patients. These women and girls were hospitalised as sufferers of hysteria, which could be characterised as an illness of uncontrollable emotions, and yet he was seemingly able to command them to do exactly as he wished.

On stage Charcot demonstrated how to provoke an attack of hysteria in a woman, then “switch” her “off” by pressing her ovary; he would put her into a trance where her limbs and facial expressions would hold rigid when manipulated into place, giving the impression of a living doll. During the most animated part of the lecture, Charcot’s subjects were put in suggestible states and made to act out whatever scenario came to the doctor or his assistants: she was walking in a park, a soldier in battle, a fine lady, a dog. Whatever was asked of her, the woman performed as though truly living the experience, emoting fully and artlessly. The watchers were amused, moved, titillated – and certainly impressed by the mastery Charcot had over these otherwise ungovernable women. More than just creating a troupe of automatons, Charcot was gathering insights into hysteria, a condition that had eluded medical understanding for centuries. His approach was revolutionary, yet controversial. And he had the eyes of the world upon him.

The showman

Dr Charcot was a highly respected doctor whose researches into the body’s nervous system helped identify multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s and Lou Gehrig’s disease, to name a few. These achievements were all the more remarkable given his working class origins – the only son of four that his parents could afford to educate. His rise in the medical profession was down to intelligence and hard work, not a foot up through family connections. But rise he did. By middle age he was comfortably established, having married a rich woman, and they were living in a chic suburb of Paris with their two children. It was at this time, in the 1860s, that Charcot took on the position of chief physician at the Salpêtrière, and embarked upon a new stage of his career.

Once an institution providing housing for women who had no place in society (the disabled, mentally ill, prostitutes and orphaned children), the Salpêtrière served as a female prison for a time before being transformed into an insane asylum. In one dark episode during the French Revolution, a mob stormed the Salpêtrière to release prisoners but ended up dragging out some 25 madwomen in chains and murdering them in the street. The 19th century saw a great deal of improvement in both the treatment of the mentally ill and the living conditions of the women being treated there. This reached a new level of respectability with Charcot’s arrival and transformation of the Salpêtrière into a pioneering teaching hospital with a new neuropsychiatry department.

For while the great majority of the hospital’s patients lived in the asylum, those who suffered from hysteria were based in the neuropsychiatry ward. This was because Charcot held the unorthodox view that hysteria wasn’t a mental illness; rather he believed that it had physical – specifically neurological – origins. What’s more, he even argued that hysteria wasn’t a female-only condition, and that men could suffer from it too. But at Salpêtrière it was women, not men, that Charcot had access to. Some of them, a certain favourite few, would go on to become living case studies that he would display during his public lectures on Tuesday afternoons.

Hysteria: a mystery malady

Before going any further, it would be useful to understand just what hysteria is – or rather was, because hysteria no longer exists as a medical condition (it came under scrutiny in the early 20th century before being excised from medical books in the 1980s). But that’s not a straightforward task. The difficulty is that so many ailments were attributed to hysteria that it became a rather nebulous condition, a kind of catch-all diagnosis for a whole range of symptom experienced by (overwhelmingly) women. Classifying such a condition in a way that was universally accepted was impossible but, from Charcot’s point of view, the symptoms most associated with hysteria included:

- fainting

- paralysis

- spasms

- convulsive fits / seizures

- hallucinations

- pain

- paralysis / numbness

- anxiety

What is understood now is that women who were considered hysterics were likely suffering from a range of conditions, from epilepsy to various mental disorders. At the time, however, hysteria was the medical community’s best guess and Charcot, in good faith, was determined to discover the pathology of the disease.

Aiding him in this endeavour were the patients of the Salpêtrière’s neuropsychiatry department. The women were poor, working class, and coping with patterns of behaviour that had made life on the outside untenable. Often admittance to the hospital was a last resort for them and their families. Living conditions in the hospital were not luxurious – at times it was barely hygenic – but the hysterics’ ward was considerably more comfortable than the asylum. The hysterics, and especially those who Dr Charcot favoured, had a priviliged position in the hospital, one they wanted to hold onto. Blanche, who would become Charcot’s muse, once found herself sent to the asylum for seven months as punishment for misbehaviour. She learned that to cross Charcot was to risk everything, and never made the same mistake again.

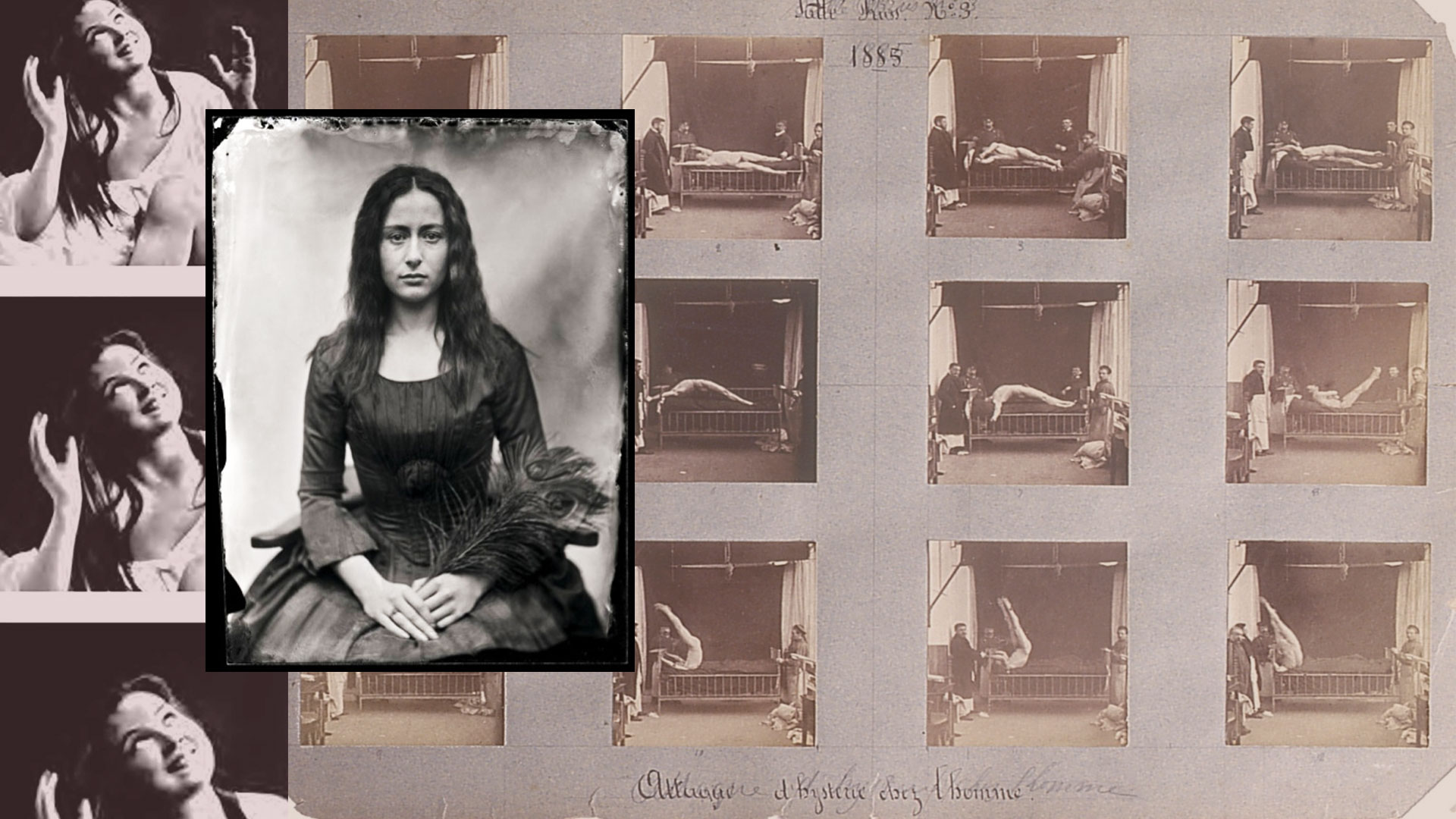

And so Charcot observed the hysterics, studied their behaviour before, during and after fits of hysteria. He noted the mood changes, abdominal pains and visual disturbances that preceded an attack, then the violence of the hysteria, how the patient would seem to change personality, raving uncontrollably, jerking out limbs, experience paralysis and faint. He recorded all this in meticulous notes, in drawings (he was an accomplished artist) and in hundreds photographs, building a definition of an elusory sickness whose very existence would be in doubt within a generation. Still, he created medical portraits of these women, finding commonality in their behaviour, and drawing conclusions based on the patterns he found.

Among the hysterics, there was one woman who stood out. Her symptoms chimed perfectly with the definition of hysteria that Charcot was writing, so much so that she became something of a model for him: a living embodiment of the condition he was describing. By her very existence she proved his theory correct. She was known as the Queen of the Hysterics, and her name was Blanche.

The perfect hysteric

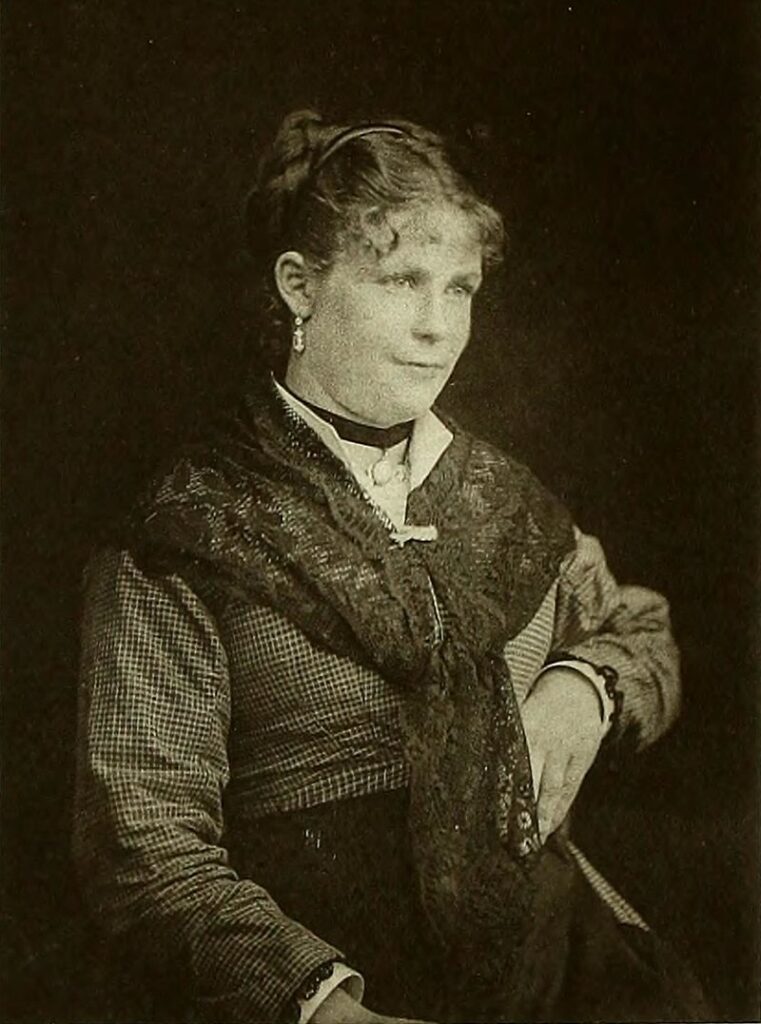

Marie Wittman entered the Salpêtrière in 1877, a few weeks after her 18th birthday. She entered as an epilepsy patient, having suffered seizures since early infancy. The condition ran in the family and had killed five of her eight siblings. By her early teens, Marie was having frequent epileptic attacks at night. Even aside from this, her life was extremely difficult with her father confined in an insane asylum and her mother supporting the family as a linen maid. When Marie began working at 12, her employer sexually harassed her, culminating in an attempted rape that led her to run away. Over the course of the next few years she entered into sexual relationships with other men, including the employer to whom she had been forced to return after the death of her mother when Marie was 15. Her seizures were on the point of being debilitating, making it impossible for her to keep down a job, when she sought treatment at the Salpêtière and came under the care of Dr Charcot, who soon reclassified her as a hysteria patient.

At the hospital, Marie’s attacks would last for hours at a time and, as Charcot noted, there were distinct phases within each one. The first was characterised by a stiffness of limbs, jerking movements and foaming at the mouth; next was a period of musclular contractions during which she would hit her head off a pillow; finally she became delirious, acting out scenes from her life – often sexual encounters. It was in this final state that she often called out the name “Blanche”, possibly the name of her dead sister, and earning herself the same nickname in the hospital.

Charcot took great interest in the phases that Marie, now “Blanche”, experienced. He used them to form the basis of his theory about the progress of hysterical attacks – and would demonstrate them during his public lectures. Because what was peculiar about Charcot’s relationship with Blanche, and his other hysteric patients, was that he had developed ways of controlling their behaviour: of initiating and curtailing both fits of hysteria and the different phases within them. His way of doing this was sometimes physical. With Blanche, pressing on her ovary could stop or postpone a crisis. Charcot even had a contraptions invented – a kind of belt that a person could wear – that would apply pressure to her ovary, alleviating the symptoms. Blanche would wear it for hours at a time, though its removal was followed by an attack. The regularity of reactions allowed Charcot to exploit her for his performances – removing the device during lectures, for example. An observer said he played her like a piano.

However successful this belt was, it paled into insignificance next to Charcot’s other method of controlling hysterics, the one that earned him the notoriety with which he is viewed today. It was by using hypnosis that Charcot claimed to derive insights into the hysterical condition, to be able to study and classify it the way he did with other neurological illnesses. This power over his patients minds may have made him greatest in the eyes of his peers, but it rendered the women in his care all the more vulnerable – and nowhere more so than when on stage.

The hypnotism show

Hypnotism has been used by humans for centuries and, though it enjoyed a resurgence of popularity in the 18th century, by Charcot’s time it had been largely discredited in western science. Charcot’s adoption of the hypnotism in his work with hysterics gave the maligned practice a great deal of credence – among his supporters at least (it was a polarising subject that remained a matter of fiery debate).

What was unexpected about Charcot’s use of hypnotism, from a modern perspective, is why he was using it. In these days of mindfulness (a sort of self-hypnosis) being used as a technique to combat anxiety, we might expect Charcot to be using hypnotism to treat hysteria – perhaps reducing the strength of an attack, or attempting to reach troubling experiences that might have contributed to its cause. But not at all. In fact, he hypnotised patients to induce a state of hysteria.

Again, his reasoning is likely to surprise someone in the 21st century, but what Charcot believed was that hypnotism was a form of neurosis that only hysterics could experience. In short: only hysterics could be hypnotised. Furthermore, a hysterical attack was actually a self-induced hypnotic state. Therefore he theorised that a hysterical patient who has been hypnotised is exhibiting the exact same behaviours as she would during a naturally occuring crisis – the only difference being that one has been provoked and the other is spontaneous. By creating this same state himself (i.e. hypnotising hysterics) he would be able to study hysterical symptoms in ordered, laboratory conditions.

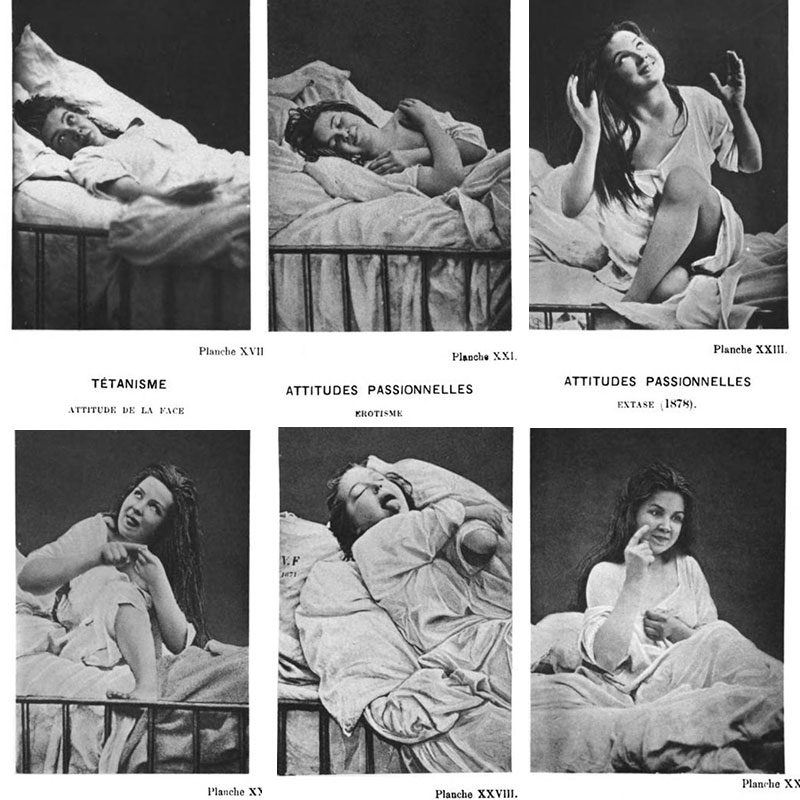

And that’s exactly what he did. Aided by his team of doctors and technicians, Charcot had patients photographed while hypnotised and displaying attitudes typical of a hysteric – the positions she adopts, the mannerisms, the facial expressions.

Charcot described the hypnotic state as being in three phases: catalepsy, lethargy and somnambulism.

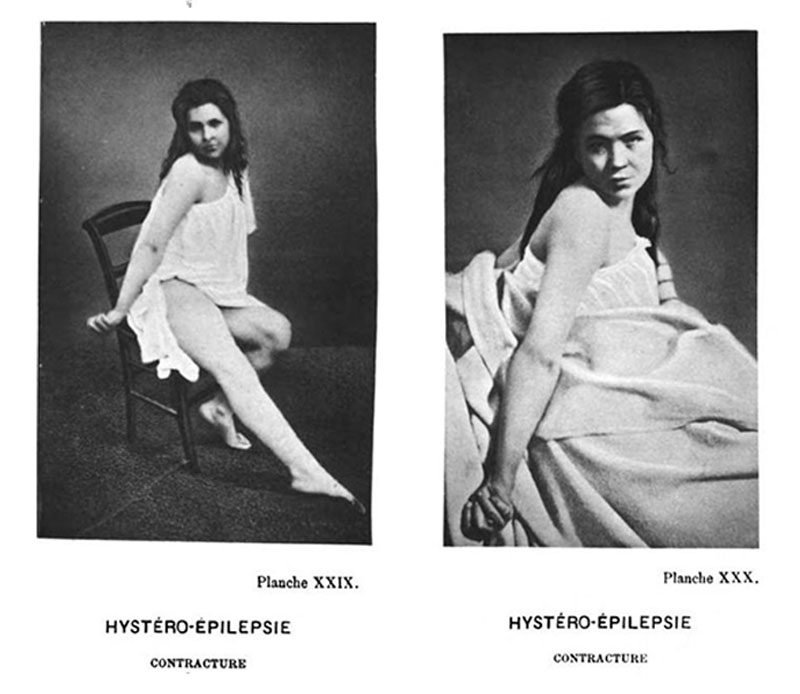

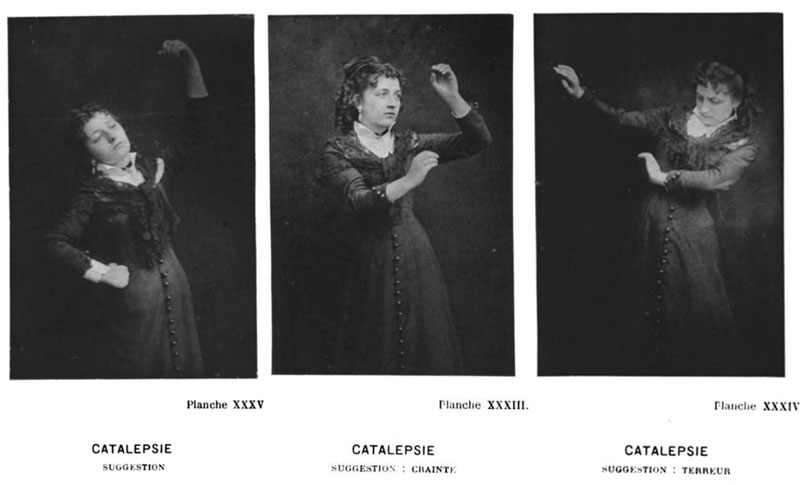

Catalepsy was brought about by shining a light into the subject’s eyes, or making a sudden loud noise. In the cataleptic state, her eyes are open but she otherwise appears to be anesthetised; she does not react to outside stimuli and her body is numb. To test this apparent insensibility, doctors inflicted pain on the women: inserting needles deep into their bodies, or by cutting and burning their skin. A true hysteric – one who is not faking it – remained oblivious to the hurt.

The other feature of catalepsy was an eery way in which the women could become frozen, fixed board stiff in unnatural positions. The doctor would demonstrate this by, for example, lifting her arm up above her head. The hysteric patient then holds this in a rigid, doll-like manner until the doctor moulds her into a different pose. As was often remarked at the time, the hysterics on stage were like living automatons, human machines under the control of the man manipulating their bodies.

What’s more, when the cataleptic subject was in positions that represented an action (say, kneeling in prayer, blowing a kiss) then the subject’s facial expression would animate to adopt to the one corresponding to the act. A look of piety accompanied the prayer pose, a tender smile with the kiss. The reverse was also true. Charcot could physically manipulate the patient’s face into a smile with his hands and she would adopt the kiss-blowing attitude.

Sometimes an electric facial probe (invented by Charcot’s mentor Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne) was applied to the patients’ faces, stimulating the nerves into a facsimiles of natural facial expressions. Again, the body assumed the pose corresponding with the emotion that had been shocked in place. Not only were they living dolls, they were now powered by electricity.

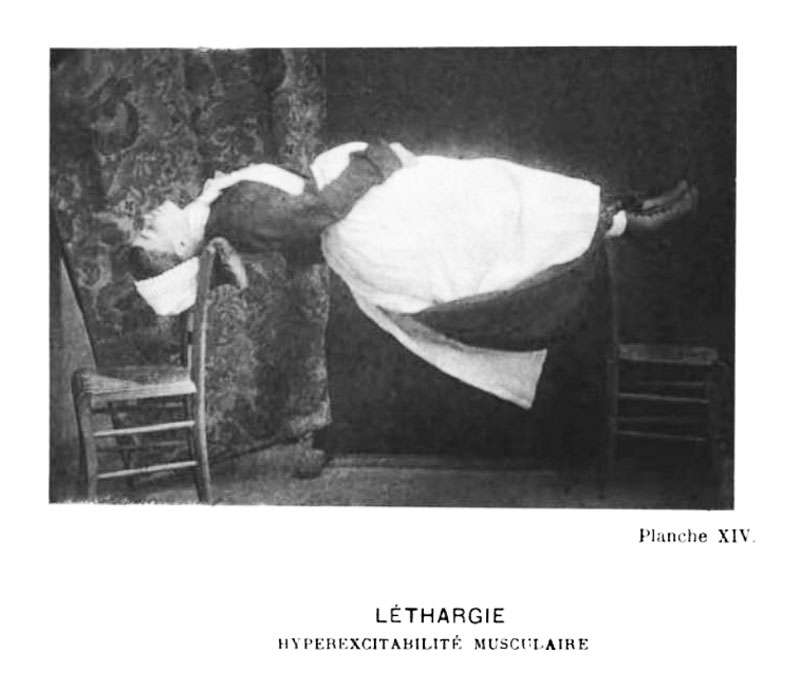

The next stage of hysterical hypnosis, as defined by Charcot, was lethargy. This could be achieved by simply by closing the cataleptic subject’s eyes – she would then enter into a kind of deep sleep, though remain standing. In contrast to the cataleptic state, a lifted arm would no longer remain in place, instead it would fall to the subject’s side. What made this state particular was how the patient’s muscles were capable of flexing to the point of absolute rigidity. To bring this about, the doctor needed only to stimulate the muscles with a light touch for them to contract and remain flexed indefinitely. As with the cataleptic state, doctors would go to extremes to weed out fraudulent hysterics, pushing their subjects to adopting and maintaining uncomfortable contortions, positions that would challenge even an athlete. To waken the successful hysteric, the doctor need only open her eyes in a bright room or blow in her face.

Finally, came somnambulism, where hypnotised hysterics were seemingly awake but susceptible to suggestion – a state that was exploited for great dramatic and comedic purposes at the Salpêtrière. On awakening the patient from the lethargic state, the doctor would press on top of her head or stare into her eyes to put her under his control. These working-class women were told they were aristocrats, or soldiers, or animals – anything they were not – and they would act accordingly to the delight of the audience. Classic tropes of stage hypnotists were employed: the women ate lemons like they were sweets, they recoiled in fear from snakes that didn’t exist, sniffed amonia and said it was perfume.

So far, so vaudeville. The display was curious, entertaining, but harmless. (The possible degradation of the performers didn’t seem to be a consideration for Charcot, his colleagues, or the audience.) Where things became problematic was when the suggestions became sexual in nature. In one incident, a hypnotised woman was told by medical students to undress and take a bath (she was stopped before she could remove her underwear).

Another stunt performed publicly during Charcot’s lectures was the “mariage à trois”. In it a hypnotised female patient woman was told to imagine herself divided down the centre of her body, each side being a different woman, and that these women have their own husbands. The “women” were told to enjoy the caresses of their husbands but reject the advances of another man. Two male lab assistants played the husbands, caressing one side of her body to her evident pleasure. But if, as the “husbands” had been instructed, they touched the other side of her body, the patient would repel them forcefully.

All this – remember – is taking place on stage before an audience of men, all in the name of medicine.

The public lectures at the Salpêtrière with their audience of Belle Époque glitterati were undoubtably a success, but appreciation of Charcot’s work with hysterics was not universal. Some critics were very vocal in their dissent, doubting the validity of Charcot’s experiments. It was said that hysteria, as Charcot defined it, existed only within the conditions he had created at the Salpêtrière. Worse still, the symptoms exhibited by the hysterics were were fake, manufactured to fit Charcot’s theories. The hysterics, and Blanche in particular, were dismissed as actresses either working under Charcot’s instructions or fooling the great man himself. So which was it?

The great pretender

Accusations of fakery were levelled at Dr Charcot during his lifetime but increased markedly after his sudden death in 1893, when opponents felt less inhibited by the great man’s influence and reputation. Attacks came thick and fast, to the point that Charcot’s entire body of work was tarnished because of his association with hypnotism and hysteria. Given the fact that today hysteria is no longer considered to be a real disease, we have the luxury of hindsight in looking back and asking just what was going on with these women who could perform extraordinary feats on command.

Another thing that changed after Charcot’s death is that Blanche stopped having hysterical fits. Though she maintained to her deathbed that she wasn’t faking (she said it would have been impossible, Dr Charcot was too smart, he would have caught her out) their cessation is very telling, it strongly suggests that she was to some degree performing for him when having an attack.

It is certain that the symptoms that Blanche entered the hospital with were real. What is also true is that, over the years, they adapted to fit Charcot’s definition of a hysteric. Even if Charcot was not explicitly coaching his patients how to fit the hysteric model, they were surrounded by clues of how a hysteric should behave. The walls of the ampitheatre where Charcot lectured were covered in patient photos depicting characteristic poses that hysterics adopt in various states of attacks. It would be easy for the female patients to imitate the physical gestures and expressions on display, whether intentionally or not.

What seems likeliest is that Charcot created a definition of a hysteric based on certain behaviour he observed in his patients. These same patients began matching this description – responding to cues provided by doctors, copying their fellow hysterics, picking up on evidence in their environment – which served to prove his definition to be true. Charcot would naturally be pleased and he rewarded his patients for their successful imitation. Remaining in the hysteria ward was a reward in itself but for the “best” hysterics, even more favour was shown in the form of attention from medical staff, and even the chance to perform to the public. (The reverse was also true: being sent to the insane asylum for not fitting the mould was a real threat, as Blanche knew from personal experience.)

There is little to suggest that deliberate deception was at play; rather that within the Salpêtrière a kind of internal feedback loop was at play that no one had the wherewithal to break. The women weren’t duping Charcot as much as they were trying to fit as best they could into this peculiar, self-contained world. Ultimately Dr Charcot, as the man with all the power, was responsible. Had he studied hysterical patients outside his own hospital – a control group, say – the results would have been so remarkably different that he would have been forced to question his methods. As it was, death saved him from seeing his work destroyed.

A new beginning, a tragic ending

With her protector gone and her condition improved, Blanche Wittman found a new role for herself within the Salpêtrèrie hospital, that of assistant in the photography laboratory, helping develop the very photographs that she had once been subject of. After that she moved onto the radiology department where she worked as a technician. It was the early days of this science and the dangers of X-rays were not yet understood; Blanche was exposed to carcinogens through her handling of equipment, leading to radiation burns on her hands and arms. First one finger was amputated, then another and another; doctors kept cutting the diseased areas off, higher and higher, until her entire arm was removed. Then the same amputations began on her other arm. Both Blanche’s arms were gone before she died in 1913 at the age of 54.

Sources

My main source for this post was Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris by Asti Hustvedt (Bloomsbury). I would have loved to have included information about the other hysteria patients, as detailed in this book, but couldn’t fit it in. I’d therefore highly recommend reading this book if you’re interested in delving in deeper into this subject.