Murder on the Paris Métro: the double life of Laetitia Toureaux

It was past midnight on Thursday the 13th of May 1937 when Laetitia Toureaux exited the métro station and began making her way home. She had been working that evening in the cloakroom of L’As de Coeur, a nightclub in central Paris, and had to get up early next day for her shift in a shoe wax factory. Though the hour was late and the streets were quiet, Laetitia was not afraid. Because of her part-time work in the club, she was used to moving around the city alone at night – and, besides, it was only 50 metres (164 feet) from the Pierre-Auguste métro station to her home a 3 rue Pierre Bayle, a short street that leads to the famous Père Lachaise cemetery. This night, however, was not to be like all the others.

She had just arrived in front of her building and rang the doorbell for the concierge to let her when a man attacked her from behind. Laetitia turned and hit her assailant several times. In the meantime, the door opened and Laetitia was able to escape to safety into the hallway. The man fled.

Though an alarming incident, Laetitia appeared to laugh it off when she related the story to four employees of the Métro station, whom she knew through her regular use of the trains to-and-from work. “I carry an umbrella with me now!” she joked to the concerned station manager Monsieur Martin, also a neighbour, in reply to his offer to walk her home at night. This conversation took place on Saturday the 15th of May. The following day Laetitia Toureaux was murdered on the Métro, in an assassination-style killing that has never been officially solved.

What are we to make of this attack, in light of its proximity to the murder? Was it an earlier, failed, attempt to kill Laetitia? Police investigators was quick to dismiss any connection but, given their failure to track down the killer, their decision not to pursue it further is questionable. If it was the same person or persons behind both attacks, it reveals that someone was determined that Laetitia should die, and speaks to the importance of discovering the motive behind it. From the style of the murder – the single, precise blow of the dagger into her neck, at close range and in public – police believed from the outset that this was the work of a professional hitman, not a homicidal lunatic or jealous lover. But, why would anyone want Laetitia Toureaux dead? She was a factory worker and part-time coat check girl, a widow who was close with her working-class Italian family, and about whom no-one had a bad word to say.

Only, as the police and press were soon to discover, nothing about Laetitia’s life was quite that simple. Before even the first week after her murder had elapsed, newspapers were full of stories about Laetitia’s double life, revealing details of clandestine work and connections with powerful men that she had kept hidden from even those closest to her. Could the riddle of her death, the “locked room murder”, be answered by looking into the secret life of Laetitia Toureaux?

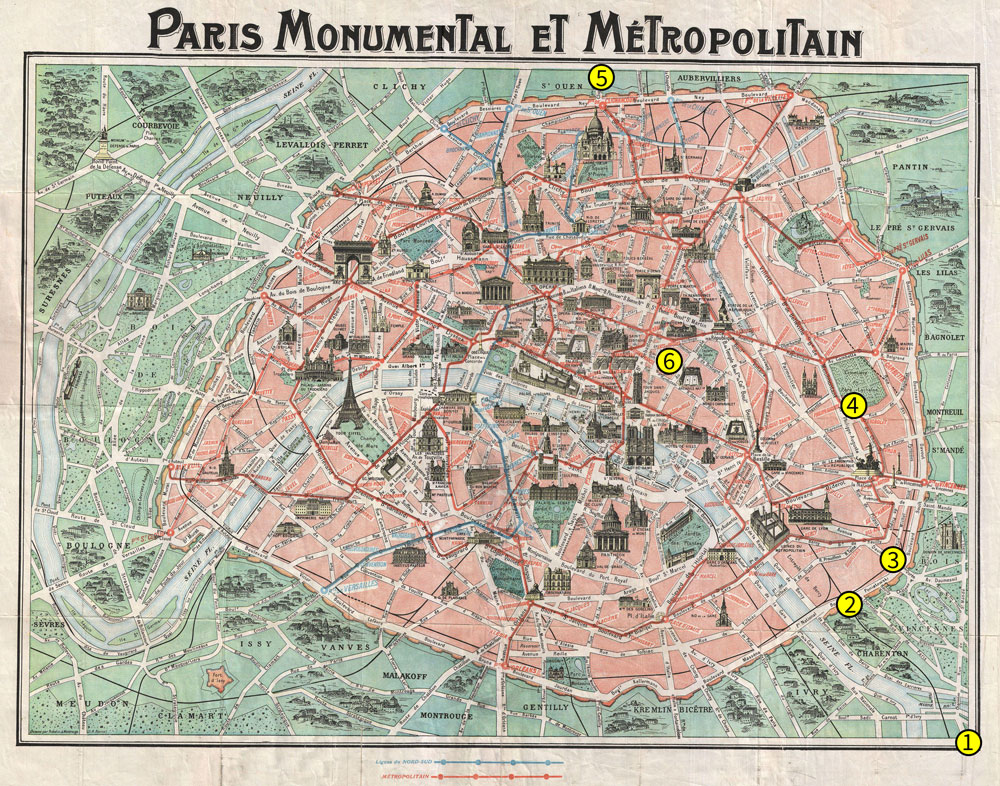

(1932 Robelin map of Paris via Wikimedia, public domain)

Laetitia Nourrissat was born on the 11th of Spetember 1907 in Val d’Aoste, north Italy, a mountainous region close to the border with Switzerland and France. In her early teens, she moved with her mother, three brothers and sister to Paris, leaving behind Laetitia’s father in Italy. Laetitia was the only one of the siblings to maintain contact with their father, and corresponding and visiting him up until her death. The Nourrissat family lived in an area of Paris popular with Italian immigrants, many of whom fled their homeland in the 1920s when Mussolini came to power and cracked down on political opponents. As the Nourrissat children grew up and got married, they remained in close proximity to one another, eating regularly together.

In 1926, aged 19, she began work in a pottery factory where she met and began a relationship with Jules Toureaux (35), the son of the factory owner. The couple eventually married in December 1929 but in secret: Jules’ parents would not have approved of him marrying someone from a lower social class, and were only to find out that he had a wife in the weeks before he died of tuberculosis in March 1934.

The result of Jules’ subterfuge – including his living partly at his parents’ house, partly with Laetitia in his batchelor’s apartment – was that Laetitia was left with no money and no assets when he died. The loss of her husband was devastating for Laetitia; their situation was unusual but, from all accounts, it is clear that they were devoted to one another and Laetitia mourned him deeply. She moved into the tiny apartment in rue Pierre Bayle with some furniture taken from the marital home but little else. She had to find work to support herself, and fast.

At the time of her death in May 1937, Laetitia was employed by Laboratoires Maxi, a company that manufactured shoe and hair wax, in their Saint-Ouen factory in the northern suburbs of Paris. She was popular among her coworkers and appreciated by her bosses. Initially she labelled jars on the factory floor before being promoted to the showroom where she would demonstrate the company’s products. She worked Monday to Friday, leaving home at 6.30 am and returning at 6 pm.

In addition to this, she worked three nights a week in a nightclub, L’As de Coeur, in the Temple district of Paris, returning home on the last métro before the line closed. A punishing schedule considering that she would be working the next day but, as a widow with limited means, it was necessary to make ends meet.

Though Laetitia worked in the nightclub’s cloakroom, she would also dance with paying customers. Men were able to purchase dance tokens that they could exchange for a turn on the dancefloor with one of the club – or bal musette – employees. A socialable woman who loved dancing, Laetitia enjoyed this part of her work; it helped take her mind off her grief for her husband for a time at least.

Details of Laetitia’s emploment were made public in the immediate aftermath of her murder but on the Thursday of that same week, news of a different line of work made headlines in the press. It was revealed that Laetitia had been working for some time as an investigator for a private detective agency. Her employer, Georges Rouffignac, came forward to say that she worked for him from October 1935 until November 1936 and said that she was thoroughly adept at the job, seeming to already know the profession. Rouffignac explained that Laetitia’s tasks had been innocuous: following philandering husbands, establishing home addresses, for example. But in spite of these assurances, the new theory that Laetitia had been killed in revenge for her part in an investigation took hold of the press and public’s imagination.

Adding flame to the fire was the fact that Rouffignac was not a reliable source of information. In interviews he backtracked on his opinion of Laetitia’s quality of work (she was professional, then she was sloppy), he revised the length of time she had been working for him (from 13 months down to 6 months). But eventually he revealed that his agency, in addition to exposing adulterous spouses, also specialised in infiltrating workforces and worming out political agitators. A series of crippling strikes in the summer of 1936 had seen workers occupy factories and the potential for similar shutdowns was a real concern for industrialists. One of Rouffignac’s personal friends, a factory owner, was in this exact position so Rouffignac offered him a detective to join his workforce as an undercover agent. Laetitia began work at the Maxi factory in November 1936.

Though a well liked member of the team, Laetitia was, in fact, reporting back on anyone with socialist leanings or agitating for action against management. Her ease with the duplictous nature of spying reveals that there was more to Laetitia’s character than was apparent at first sight. But her placement at Maxi factory wasn’t the only area of her life that was controlled by Georges Rouffignac. It turned out that he also secured for her her work at l’As de Coeur. At this time in Paris, cloakrooms were often used as drop off points for letters that could otherwise be intercepted. Having an operative who was able to go through the contents of coat pockets was a valuable resource for Rouffignac.

It seemed that the more one looked, the greater the importance Georges Rouffignac had in Laetitia’s life. It extended even into her social life. One of the notable things about Laetitia that was commented upon from the outset was her membership of La Ligue Républicaine du Bien Public, a prestigious liberal organisation with anti-fascist aims. She had been wearing her red and black membership medal prominently on her coat lapel on the evening she was murdered. The bus driver who took her from Maisons-Alfort to Porte de Charenton noticed it and understood its signification.

While this appeared to present Laetitia as someone with moderate political views who was concerned about the uprise in far right sentiments in Europe, this interpretation could be viewed in another light when it became clear that Rouffignac was one of her sponsors in her membership application. What’s more, she joined the League just one month after she started at Maxi and L’As de Coeur. The timing, her sponsor – and her apparent otherwise lack of interest in politics – made it look like she had been placed in the organisation as a spy, just as she had in her places of work.

There was another curious fact about her membership: the second sponsor was an Inspector Cettour, a police officer. What was his relationship with Laetitia and Rouffignac? Of Rouffignac, it isn’t difficult to imagine how the two men could have come into contact, even helping one another out in investigations. Cettour’s link to Laetitia is more obscure – the French police’s report into Laetitia Toureaux’s murder drew an enigmatic silence on this point. But it did state that Laetitia had been a police informant for many years – going back to when she was a teenager.

Spying seems to have been a familial trade, one that Laetitia learned from her mother, who had been informing for the police since her arrival in Paris in the 1920s. To modern ears, this may seem bizarre but in the interwar period in France, political tensions were high with extremist fascist and communist ideologies competing for precedence, and police used ordinary people to keep an eye on agitators or sympathisers. In the Italian emigrée community, it wasn’t just the French police that coluded or coerced people to snitch on their neighbours but Mussolini’s government too. The Fascistas had an active interest in what its countrymen were doing abroad. Police investigating her death found that Laetitia had made several secret visits to the Italian Embassay to meet with government officials. They were now questioning whether Laetitia was a double-agent, spying for the French police and Mussolini’s party members. Laetitia was mixing in dangerous company – but this was only half the story.

In 1936, France had a Socialist government while neighbours Italy and Germany were run by the Fascist and Nazi parties, and another neighbour, Spain, was entering into a 3-year civil war that would end with victory for Franco’s Nationalists. With an international war brewing, France’s future political alliance was with the Allies (The United Kingdom, The United States and the Soviet Union). However, if France’s Socialist government were to be overthrown by a group favourable to Italy and Germany, the Pact of Steel between those two nations could be expanded to include France, a linchpin for control of Europe. This wasn’t just some academic theory. There was a violent, revolutionary group in France in 1936 and 1937, that was acting to install its own puppet government and change the country’s course. They became known as La Cagoule, the Hooded Ones. This secretive organisation is known to have carried out a series of thefts, bombings and murders in 1937. The were well funded, well organised and well connected. They were also ruthless in tracking down and killing anyone who spoke out against them. In the months leading up to her death, Laetitia Toureaux inflitrated the gang – and betrayed them.

Next time: Laetitia Toureaux and the French Fascists

Part one: Murder on the Paris Métro: the unsolved death and mysterious life of Laetitia Toureaux

Sources

My main source for this article is this excellent book Murder in the Métro: Laetitia Toureaux and the Cagoule in 1930s France by Gayle K. Brunelle, Annette Finley-Croswhite (LSU Press) which helped fill in lots of blanks and straightened out some of the conflicting information I’d come across. I’ve also read a great many contemporary newspaper accounts via RetroNews.fr, the excellent French-language newspaper catalogue run by the French National Library. Finally, a big mention should go to the site Crimocorpus.org, a Museum of Crime, Justice and Punishment, via which I was able to access Detective (various issues), a French-language magazine that covered the story in great depth.

Pingback: Murder on the Paris Métro: the unsolved death and mysterious life of Laetitia Toureaux – BEST FRANCE FOREVER