The kiss that caused a riot

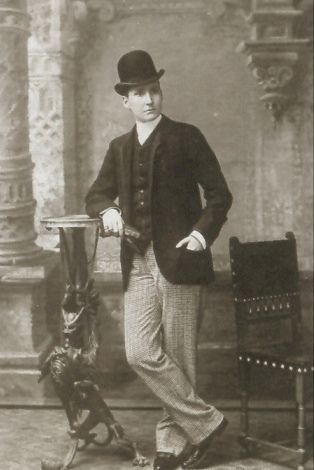

It was the suit. A simple, brown trouser suit; elegant and – knowing the aristocratic wearer – doubtlessly expensive but an otherwise unremarkable item of clothing. All the same it was the suit that got the audience whistling and jeering right from the get-go. The problem was that, as soon as the curtains opened on the stage at the Moulin Rouge, the audience recognised the actor on stage as being the writer of the piece, and this actor in a plain brown suit – up there in lights in front of a packed house – was a woman.

If the reaction to the opening was bad, it was about to get far worse. Not only had Mathilde de Morny dared to perform as a man, she was about to go even further in expressing her sexuality publicly in a way that just didn’t happen back then, even in the hedonistic Paris of 1907. Same-sex kisses have the power to shock now. The on-stage kiss between Mathilde and her fellow performer – and real-life lover – Colette was about to enrage the Parisian audience to the point that police intervention would be needed to prevent a riot.

But back to the suit, for a moment. It wasn’t merely a costume. At the time this scandal took place, Mathilde de Morny was 43 years old and she had been wearing “men’s clothes” for most of her adult life. With her short hair, boots, three-piece suits and cigars, Mathilde – or Max, as she was often known – was flagrant, unapologetic even, in her preference for men’s attire. It wasn’t just conventions she was breaking in doing so, it was the law. From the 1800s to 2013 (“2013” is not a typo), it was illegal for women to wear trousers in France. If a woman wanted to do so – to ride a bicycle, for example – she was meant to ask the local police constabulary for permission.Mathilde was fortunate enough to be of the very highest society with family money behind her. Rules don’t apply equally across all spectrums of society. That’s not to negate her personal bravery or suffering she endured as a result of her lifestyle, just to say that Mathilde had social and financial power enjoyed by very few.

She was born on the 26th of May, 1863 in Paris, the fourth child of a French duke and a Russian princess. Her father, Charles de Morny, was the illegitimate son of the Queen of Holland whose half-brother – Mathilde’s uncle – would go on to become Emperor Napoléon III. While her mother, Princess Sophie Troubetzkoï, could claim no less than Czar Nicholas I of Russia as her father, albeit illegitimately. The seemingly harmonious union was cut short by the death of Charles de Morny when Mathilde was not even two years old. Mathilde’s mother remarried four years later to a Spanish nobleman and large parts of Mathilde’s childhood was spent in Spain.

Mathilde’s relationship with her mother was cold. Her mother’s nickname for her was “tapir” in reference to her long nose. But she enjoyed her stepfather’s company and the two would hunt together in the Castille countryside at his estate. She liked riding, flamenco dancing and bullfighting. One of the bullfighters she admired was Dolores Sanchez, “La Fragosa”, the first female bullfighter to dress in the male costume. It was also in Spain where she had her first sexual experience with a young servant girl. There was a price to be paid for the encounter – a financial one – as her lover blackmailed her afterwards.

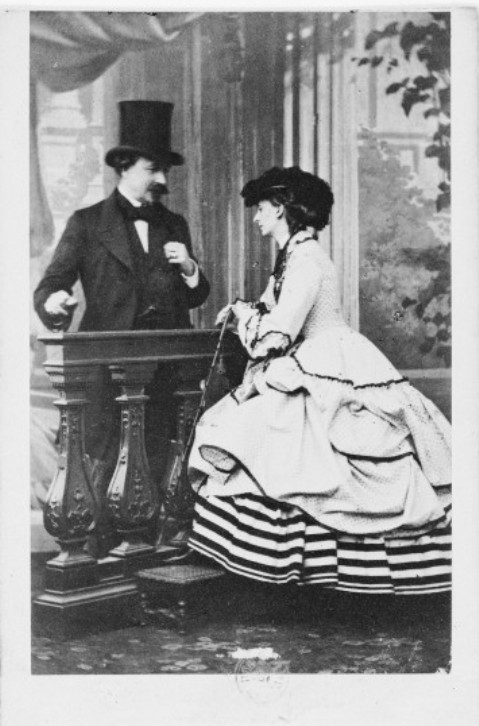

In 1881, at the age of 18, Mathilde married Jacques Godart, the Marquis de Belbeuf, and moved into his château in Normandy. From the outside, their relationship appeared conventional but this wasn’t at all the case. He was homosexual while she was becoming more open about her preference for women. It was a relationship that allowed them both a degree of freedom and the two remained on good terms even after their divorce in 1903.

Rich and free to do as she pleased, Mathilde pursued romantic relationships in Paris, including one with the famous courtesan Liane de Pougy. Some accounts say that Mathilde “won” Liane by fighting a duel with a rival male lover, triumphantly exposing her breasts at her victory to humiliate him further – defeated by a woman. Mathilde was proud of her physical strength and was one of the first people to install fitness equipment into her Paris apartment. She would invite friends to watch her work out, something she apparently did naked, or so the story goes.

Her dress was masculine in style by this time. To get round the laws (social and legal) forbidding women from dressing as men, she had outfits custom made that had, say, a detachable skirt that could be removed to reveal trousers when she was in right-minded company, allowing Mathilde to dress according to her preference while paying heed to norms of the day. It was only after the death of her mother in 1896 that she abandoned women’s clothing altogether and wore bespoke Savile Row suits. Her wealth and status gave her a cosseted existence; they also allowed to exercise a kind of patronage with the women in her life. She could afford to give women gifts, take them to fine restaurants or on holiday, set them up in an apartment. In this, as in her dress, she very much adopted a male role. Mathilde preferred to be addressed by masculine names – “Monsieur le Marquis” or “Oncle Max” to her inner circle.

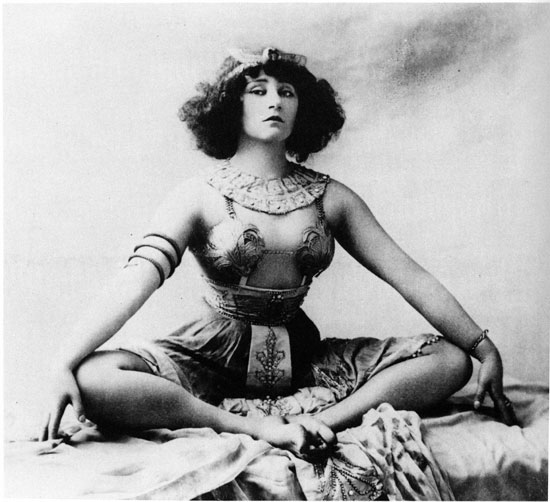

By 1906, Mathilde de Morny was 42 and had entered into the most significant romantic relationship of her life, that with Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, more commonly known as by the name she used for her writing, Colette. When they met, Colette was 33 and had recently split from her husband Henri Gauthier-Villars – or Willy – who was himself a well-known writer. She was yet to achieve the renown she would later enjoy for her writing; Colette had written a series of books about a character Claudine but, although acknowledged as the writer, the books had been published under her husband’s name and he, not she, received the income generated from their sales. And so, finding herself struggling financially after the separation, Colette turned to the stage. She began performing in pantomimes – short dramatic performances accompanied by music that used mime and dance to tell a story – and enjoyed a degree of success and certain notoriety for her willingness to wear revealing costumes or even – later – bare her breast on stage.It was during this intense period of stage work that the relationship between Colette and Missy (as Colette liked to call Mathilde) flourished. Mathilde seemed to fill a similar role to Willy in being at once a lover and an almost parental support to Colette, her “insupportable enfant” (Colette’s words), subsidising her lifestyle, putting her up in the best hotels as she toured music halls across France. Towards the end of their time together, Mathilde even bought and furnished a manor house in Brittany for them both, though left it entirely to Colette when they split a year later.

Colette’s enthusiasm for pantomimes was infectious and it wasn’t long before Mathilde followed her lover on stage. Throughout October and November of 1906, Colette had been playing a gyspy in La Romanichelle. On 27 November, Mathilde replaced the usual male lead in this production when it played at the Cercle des Arts et des Sports in Paris. And the audience reaction at seeing a woman in a trouser suit playing a male role? None. There was no outcry when they repeated the line up mid-December at the Moulin Rouge – the same venue where the incendiary staging of Rêve d’Egypte would take place just a few weeks later.

Though Colette was the writer with experience of music hall entertainment, it was Mathilde who wrote Rêve d’Egypte (Egyptian Dream), a pantomime that was to last 15 minutes. The piece is set in a study filled with dusty old books about the occult. The curtains open on a male scholar, an Egyptologist, played by Mathilde, flicking through a book. Suddenly he is overcome with phantasmagorical visions – the statues, paintings and books in the room seem to come to life. Then, from the corner of the room, the lid of a sarcophagus opens and a mummy, Colette, comes out. She dances seductively, putting him under her spell, tempting and teasing, coming closer until he is able to remove her bandages and reveal the woman beneath, coming still closer so he is able to kiss her – a kiss that will bring her back to life. At the moment of the embrace, the scholar comes to, and realises that it had all been a dream. Told like that there is little to shock or surprise in the setting or actions; the drama comes very much from who was on stage and what they were wearing.

The auditorium of the Moulin Rouge was packed on 3 January 1907. Three acts were on the bill that Thursday night with Rêve d’Egypte on second. It is certain that a great number of the spectators that night would have been drawn to see Mathilde and Colette’s debut – there had been a great deal of publicity, though not all of it welcome. Mathilde had tried to keep her participation low key; she had used the pseudonym Yssim (“Missy” backwards) when writing the piece and had been furious when the Moulin Rouge used her and her ex-husband’s family crests on the event posters. (She would later sue the Moulin Rouge, and win, for this breach.)

In addition, many articles had appeared in the weeks leading up to the performance. Colette and Mathilde were hardly strangers to the gossip pages: Colette had been one half of a literary power couple and was now making a name for herself in risqué stage numbers, while Mathilde was a cross-dressing aristocrat with family links to the highest reaches of society. And their relationship? While never explicitly stated, it was very heavily insinuated that their relationship was more than professional and went beyond ordinary friendship.

The friendship between these two women has become so indiscreet that tongues have begun to wag, and their artistic and literary relationship is now the subject of gossip…

Press articles in the lead up to the show never fail to mention Colette’s erotically charged previous performances nor Mathilde’s uncle Napoléon III. A journalist for La Patrie gleefully recounts lying his way into Colette’s home and baiting her with provocative questioning. He speculates that the de Morny family won’t allow Mathilde to perform on stage, to which Colette retorts, “La marquise de Morny is free in all her acts… She won’t give in to prayers or threats. She loves the theatre and she will do it. That’s all there is to it.”

With all this hype, it’s no wonder that a large crowd turned out that evening. But what did they expect to see? Titillation, certainly; a posh lady make a fool of herself on stage, hopefully; simulated lesbian lovemaking, less likely. What does seem certain is that a large part of the audience of Rêve d’Egypte knew that Mathilde was a lesbian who habitually dressed as a man and they attended just to show their disapproval. They planned ahead and came prepared to disrupt the performance, carrying objects to throw and whistles to blow. Even so, they got more than they bargained for.

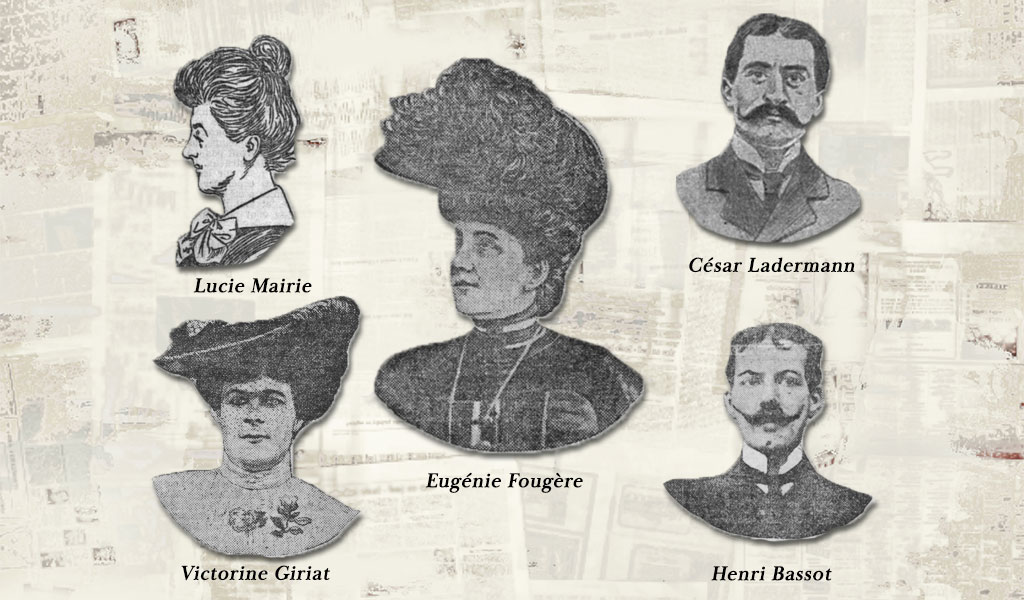

Which takes us back to where we began with the curtain lifting on Mathilde onstage at the Moulin Rouge, wearing her brown stage, in the pose of an Egyptologist engrossed in a book. The whistling and jeering was immediate. The very sight of this woman crossdressing outraged some of the audience – there were certainly supporters of Mathilde and Colette there too. As the performance began, audience members shouted insults and started to throw things onto the stage: oranges, apples, old vegetables, cigars. Colette’s entrance as she exited her sarcophagus was greeted by a bunch of turnips landing at her feet. Bravely, the women carried on. The crowd started chanting, to a popular revolutionary tune, for the pair to get off stage. Walking canes beat the floor, feet stamped, pocket whistles were blown – anything that could disrupt and put an end to this outrageous performance was used. But still the women went on. As Mathilde unravelled Colette’s mummy bandages to reveal even more flesh, the size of the items flung at them got bigger. Clouds of cushions, even small benches were hurled onto the stage. Undeterred, the performance reached its climax with a kiss between the mummy and the scholar. Furious, the audience had turned into a mob. People were on their feet, blows were exchanged. Willy, Colette’s estranged husband, took the brunt of the mob’s anger. He was standing, chastising the unruly audience members from his box when he was surrounded and attacked. Fists and sticks rained down upon him as he tried to escape. He was saved by the arrival of the police. Soon the theatre was swarming with officers who ejected half the audience, preventing a full-blown riot from erupting, though not before some invitations to duels were laid down. The performance was over but the repercussions were only just beginning.

Rêve d’Egypte with Mathilde as the Egyptologist was only performed once. The prefect of the police, Louis Lépine, allowed it to be played again the following night under a different title Songe d’Orient with a man, the mime artist George Wague, replacing Mathilde. It was a disaster. While not violent, the crowd once again whistled and shouted throughout, chanting “la marquise” for the missing Mathilde. This time it was banned completely from Paris. Two months later, Colette and George took Rêve d’Egypte to Nice for three nights where played without incident.

News of the near-riot caused a sensation in the press. Papers across France took great relish in recounting the eruption of violence at the Moulin Rouge, and in laying the blame squarely at the feet of the flamboyant marquise and her overtly sexual partner. It was one thing to be a lesbian behind closed doors, or even in select company, but flagrantly displaying homosexual relationships on stage was a step too far.

The scandal is not in the vehement protest of a disgusted public, but in the paradoxical exhibition they were presented with. If people don’t understand that their peculiar relationships shouldn’t be displayed in public, then it is right that Paris makes them hear it, even with an elementary tool like a whistle.

Usually protected by her family name, now – if anything – it attracted more negative attention. The de Morny and Belbeuf families, until now tolerant, distanced themselves from Mathilde. Later that year, Mathilde was in the news again when a woman at a party in her home was accidentally shot and killed. Mathilde had been showing off a handgun to her guests when, noticing it was dirty, told her butler to take it to be cleaned. The gun slipped from his hand, shooting off two of his fingers and hitting a guest, a Madame de Costa, in the forehead.

Attention from Rêve d’Egypte weighed on Mathilde and Colette and they weren’t able to enjoy the same kind of freedom they had before. That said, they were together for five more years and the letters from the period attest to the passion and affection they had for one another. After their split, Colette went on to marry two more times and wrote a series of highly acclaimed novels. The most famous of these, Gigi, was published in 1944, the same year in which Mathilde put her head in an oven and gassed herself at the age of 81. Though both women lived in Paris throughout Nazi occupation, they were worlds apart: Colette the feted writer, Mathilde a penniless eccentric and relic of a bygone age.

- Mathilde de Morny was given the name Sophie Mathilde Adèle Denise de Morny at birth, though she was known as Mathilde. She had various titles and nicknames: la marquise de Morny, la duchesse de Belbeuf, Max, Oncle Max (Uncle Max), Missy, Yssim. I’ve referred to her as Mathilde throughout for simplicity’s sake, even though this feminine name may not have reflected how she wanted to be seen for most of her adult life.

SOURCES

I read a lot of contemporary news reports via Retronews.fr and spent a great deal of time on Wikipedia.

This blog post by James J Conway (in English) is really interesting and well written. It focuses on Mathilde’s life and sexuality, not just on the Moulin Rouge scandal. It’s short and well worth a read: https://strangeflowers.wordpress.com/2012/06/29/dress-down-friday-mathilde-de-morny/

The second English source I used was this piece about Mathilde’s sexuality and the way it had been interpreted or misappropriated in recent years. It’s something I chose not to get too into in the post (i.e. the debate about whether she was she trans or not) but I think this article has a very strongly argued point of view and is definitely worth a read. It’s by JD Robertson on The Velvet Chronicle.

thevelvetchronicle.com/mathilde-missy-de-morny-embodied-female-empowerment

The site Amis de Colette (in French) was very useful with providing information about Colette’s theatrical career, including the REVELATION that Mathilde and Colette performed together on stage prior to 3 January. They also have lots of fantastic photos of Colette throughout the years.

amisdecolette.fr/colette/colette-sur-scene/

Scandale au Moulin Rouge by Marie-Aude Bonniel in Le Figaro (in French) is a great overview of the scandal from a historical perspective.

Finally, I was delighted to listen to a podcast featuring my favourite French TV personality Stéphane Bern because he’s just a joy. It’s called Mathilde de Morny, la duchesse qui voulait être un homme.